The Traction Gap Meets Crossing the Chasm

February 20, 2019

PUBLISHED BY Geoffrey Moore

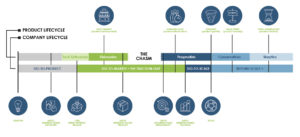

Early stage venture capital firms specialize in incubating start-ups and taking them to scale. This entails working through a series of deep changes in both strategy and operating model over a very short period of time. Many an entrepreneur, and many an investor, have lost their way during this era of “pivots.” Crossing the Chasm and The Traction Gap provide playbooks for how to navigate these changes.

Crossing the Chasm focuses on the external market dynamics that shape technology adoption, and in that context, the changes in strategy and execution needed to transition a customer base from early adopters to the early majority.

The Traction Gap, by contrast, focuses on the internal operating dynamics that shape changes in company valuations, and in that context, the actions needed to be taken with each round of funding in order to ensure a higher valuation in the next round.

More specifically, when crossing the chasm, companies need to abandon their disruption-oriented, technology-first approach to marketing and sales and embrace a market-segment-specific, use-case-first approach instead. This includes:

- Targeting a cohort of “pragmatists in pain,” who share in common a problematic use case that cannot be addressed properly by current solutions in the market,

- Committing to a “whole product” solution that fully addresses the problem use case, often incorporating products or services from third-party partners or allies, and

- Focusing a majority of their sales and marketing resources solely on this target segment, with an emphasis on domain expertise in the use case, speaking the language of the customer, and engaging with the business owners responsible for remediating the broken process.

All this is a far cry from the technology-first pitches that celebrate the disruptive potential of the next-generation offers, the ones that resonate well with early-adopting technology enthusiasts and visionary business executives, but which are judged “not ready for prime time” by the more pragmatic early majority. Thus, it is that start-up management teams, at a crucial juncture in their incubation, have to transition from the early adopter go-to-market playbook, something they know well and have succeeded at, to a less familiar, but now quite necessary, crossing-the-chasm playbook. This can often require both consulting and counseling, something that has shaped my personal practice for close to three decades and led to the formation of both The Chasm Group and Chasm Institute.

But there is a second problem to address as well, and that is, how to keep covenants with venture investors when going through this transition. These covenants are based on a simple concept. The purpose of any round of venture funding is to finance a stream of work that leads to a higher valuation of the company in question. It turns out, increases in valuation are not gradual but come instead when some important valuation factor has changed state. Classic factors include:

- Technology risk

- Market risk

- Team risk

- Financing risk

Any given round of funding is expected to change the state of one or more of these risks such that a new investor would value the company very differently from the current valuation. The Traction Gap provides a playbook for how to operationalize this idea.

Specifically, The Traction Gap calls out five valuation factors that drive venture valuation change. They are:

- Minimum Viable Category. This actually is part of the initial funding pitch and is key to securing the first round of investment. Basically, it means that the start-up has to be addressing an opportunity that can create venture returns within a venture time-frame. It not only needs to be big, it needs to be ripe for disruption—or, in Traction Gap terms, laden with “trapped value,” of the sort that the next-generation technology could release.

- Initial Product Release. This makes a big dent in technology risk, thereby creating a modest but real change in valuation. More importantly, it kicks off the search for product/market fit, perhaps the single highest risk factor in early stage investing. This is where “agile start-ups” excel their more conservative, publicly held competitors.

- Minimum Viable Product. This means different things in different sectors of the economy. In the B2B world that I spend my time in, it equates the whole-product solution to a single, compelling use case for a single target market segment. It is the boat one rows to cross the chasm, and once you have established a beachhead—meaning a handful of the target cohort have adopted the product and are giving it good references—you significantly increase your valuation because you have taken a big chunk of market risk off the table. That said, this still does not show up strongly in the numbers. Hence the need for the next milestone.

- Minimum Viable Repeatability. Now you are winning sales consistently in your target segment, and at good margins because you are providing a valuable solution to an unsolved problem in what is effectively a sole-source situation. This is the revenue growth arc characterized by a double-triple followed by a triple-double—that is, two years of 3X growth, followed by three years of 2X growth. It represents the intersection where the law of small numbers meets a truly compelling value proposition.

- Minimum Viable Traction. Here you have demonstrated that you have a going concern, a business that can, if need be, fund itself, and thus can raise money on its own terms. In parallel you have filled out your team, and you have both the scale and the growth rate to attract later stage investors. Thus, by taking team risk and financing risk off the table, you have dramatically increased the valuation of your company.

The point of all this is that, in the thrash and crash of chasms and pivots, it is easy to lose sight of these valuation inflection points and focus instead on whatever fire is burning today. Unchecked, this will lead to breaking the underlying covenant with the venture investors, from which no good can come. The whole purpose of the Traction Gap playbook is to avoid this outcome.

What The Traction Gap and Crossing the Chasm have in common is that they are both playbooks based on frameworks that predict outcomes at a time when there is not enough data as yet to know for sure.

The key to early stage success is to act before you know, and then course-correct rapidly thereafter. Good frameworks provide a platform for so doing. They do not replace an entrepreneurial team’s courage and imagination, but they do get it off to a good start.

Going forward, good frameworks continue to contribute to early stage success by:

- Creating a common vocabulary for shared knowledge,

- Taking out some of the emotion from high-risk decisions, many of which do not go well, and

- Helping dispel some of the cynicism that entrepreneurs can have about venture capitalists (and vice versa) fostering a “learn it all” rather than a “know it all” environment.

In sum, the goal of both The Traction Gap and Crossing the Chasm is to accelerate decision-making early-stage investments by cutting through a lot of the noise and eliminating a lot of the hesitation. These frameworks may not always give the right answer, but they give an answer, one that can be acted on effectively, and then course-corrected along the way.

To learn about the Traction Gap, I encourage you to explore, “Traversing the Traction Gap”. To refresh your memory regarding the Chasm, now in its third edition, I invite you to read, “Crossing the Chasm”.

That’s what I think. What do you think?

See original post on LinkedIn here.

KEYWORDS